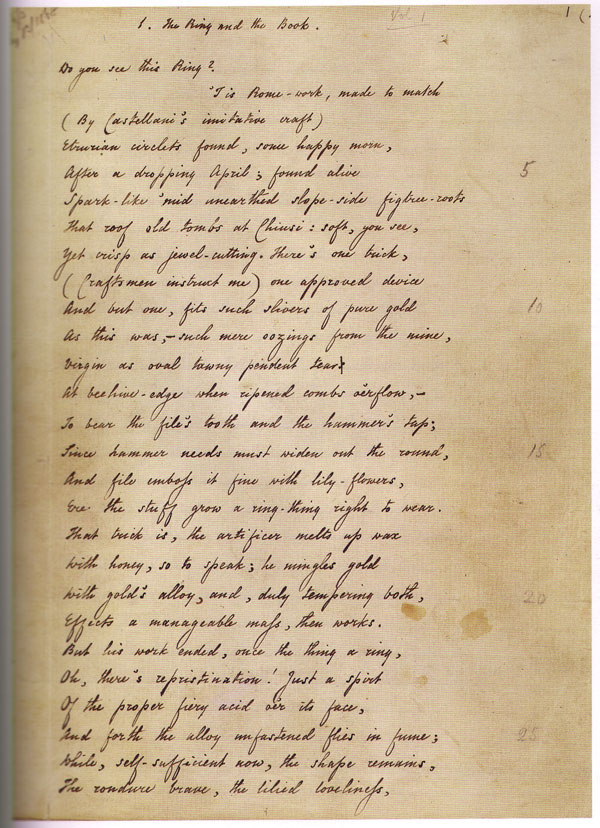

During my junior year of college, I was so confused by Robert Browning. Was the man crazy, or what? Who writes stuff like, ‘No Tully, said I, Ulpian at the best!’ (from “The Bishop Orders His Tomb,” line 100) and calls it art? Now, Elizabeth Barrett Browning is another story. What an amazing writer! I can easily identify with her beautiful imagery, voice, and style. And then there’s Robert.

During my junior year of college, I was so confused by Robert Browning. Was the man crazy, or what? Who writes stuff like, ‘No Tully, said I, Ulpian at the best!’ (from “The Bishop Orders His Tomb,” line 100) and calls it art? Now, Elizabeth Barrett Browning is another story. What an amazing writer! I can easily identify with her beautiful imagery, voice, and style. And then there’s Robert.How can you compare “Fra Lippo Lippi” with “I love thee to the level of everyday’s / Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight” (from Sonnets from the Portuguese, No. 43) I wondered. The third line of “Fra Lippo Lippi” is a good example of Browning’s unconventional style: “Zooks, what’s to blame? you think you see a monk!” Every day in my British literature class, I asked myself what this lamb-chop bearded man was talking about. He must have been insane. I couldn’t even get through one poem without cringing.

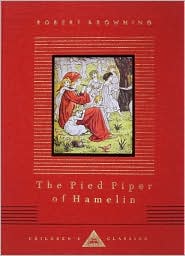

One day I decided to turn to that omniscient source of all wisdom: Google. I searched for Browning’s name, scrolled down the hit list, and was surprised to run across “‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin’ by Robert Browning” as a search result. With astonishment, my mind recalled that story I had read years ago when I was a little girl—that strange but fascinating tale of the odd piper who lured away all the children of the town because the citizens did not keep their contract with him.

One day I decided to turn to that omniscient source of all wisdom: Google. I searched for Browning’s name, scrolled down the hit list, and was surprised to run across “‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin’ by Robert Browning” as a search result. With astonishment, my mind recalled that story I had read years ago when I was a little girl—that strange but fascinating tale of the odd piper who lured away all the children of the town because the citizens did not keep their contract with him.With my eyes riveted to the computer lab screen on the fourth floor of the library, I sat there rolling Browning’s fun yet poignant lines through my mind and reliving the story that I loved so many years ago. It’s hard to say exactly why this story has always captivated me. The plot is rather unsettling when you think about it—a gypsy leading a slew of children away from their homes. As I reread Browning’s poem, I was again swept away by these alluring lines that describe where the Piper leads the children:

… a joyous land,

… a joyous land,Joining the town and just at hand,

Where waters gushed and fruit-trees grew,

And flowers put forth a fairer hue,

And everything was strange and new;

The sparrows were brighter than peacocks here,

And their dogs outran our fallow deer,

And honey-bees had lost their stings,

And horses were born with eagles' wings. (stanza XIII)

Browning’s, the piper’s, perfect place intrigued me so much—a wonderful dream of peace and joy and no more troubles.

Once I found out that Robert Browning penned the verse version of “The

Pied Piper of Hamelin” (see Note 1), he instantly shot up the charts of my personal esteem. Suddenly I wanted to understand Browning and his writing. I went back to my textbooks and began again to try to appreciate the works of Robert Browning. I read slowly and thoughtfully. I laughed, I cringed, I smiled, I cried, I got angry, I felt lonely, I felt hopeful, and many a time I was quite puzzled, but in the end I felt like I had at least scratched the surface. I didn’t become an expert, but through my research, and especially my rediscovering of “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” I penetrated in a small way an acknowledgement that Robert Browning was one of the greatest poets of the English language and that there is a reason to read and write about him and his works.

Pied Piper of Hamelin” (see Note 1), he instantly shot up the charts of my personal esteem. Suddenly I wanted to understand Browning and his writing. I went back to my textbooks and began again to try to appreciate the works of Robert Browning. I read slowly and thoughtfully. I laughed, I cringed, I smiled, I cried, I got angry, I felt lonely, I felt hopeful, and many a time I was quite puzzled, but in the end I felt like I had at least scratched the surface. I didn’t become an expert, but through my research, and especially my rediscovering of “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” I penetrated in a small way an acknowledgement that Robert Browning was one of the greatest poets of the English language and that there is a reason to read and write about him and his works.Most scholars skip over “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” because it is, as Browning himself subtitles it, “A Child’s Story.” However, based on research and my own experience with this work, I have come to believe that Robert Browning’s nursery tale, “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” has more merit than most of academia gives it.

The story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin was not Browning’s own, original tale. It was a story that had been around for centuries and one that Browning’s father had read to him over and over again when Browning was a young child (see Note 2). Years later, when little Willie Macready, the son of one of Browning’s theater colleagues, was sick in bed for weeks with a bad cough, Browning penned his verse version of “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” (DeVane 127).

The story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin was not Browning’s own, original tale. It was a story that had been around for centuries and one that Browning’s father had read to him over and over again when Browning was a young child (see Note 2). Years later, when little Willie Macready, the son of one of Browning’s theater colleagues, was sick in bed for weeks with a bad cough, Browning penned his verse version of “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” (DeVane 127).Since Browning wrote the poem originally just for Willie and with no intention of publishing it, most people dismiss the poem as something just for children. According to the critics, “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” is a work that has all the principle appeals for children: an animal story, an escape from everyday life, and a satire that makes grown-ups look foolish—in short, an unmistakably acclaimed children’s classic (Jack 83, Small xi). While I agree with critics in terms of Browning’s overall literary genius, amusing rhyme schemes, and humorous imagery, all of which form a wonderful work of literature for children, the quality of the poem I find most pivotal is that this was a beloved story from Browning’s childhood that he gave as a gift to another child. Five months after Browning wrote the poem, it was published as the final piece in his book of poems Bells and Pomegranates in November, 1842 (Erickson 81, Brooke 5). At the time of publication, I think Browning must have thought about the thousands of other children who would read this tale and love it just like he did—just like I have.

But what is it about this story that makes it so captivating? Why did thirty year-old Robert Browning still care to write about the Pied Piper? As for me, I was a college student; why out of all of Browning’s better-known “adult” works was I still so enthralled with this poem? I found an answer to this question in a Browning biography:

But what is it about this story that makes it so captivating? Why did thirty year-old Robert Browning still care to write about the Pied Piper? As for me, I was a college student; why out of all of Browning’s better-known “adult” works was I still so enthralled with this poem? I found an answer to this question in a Browning biography:‘The Pied Piper’ shows more experienced readers how sadly skeptical age has made them and reminds them of their lost childhood and its simple morals … [It is] in some sense a nursery tale for adults. (Erickson 92)

Yes, this poem exemplifies Browning’s genius of variety, free medium, metrical device, etc. (see Note 3), but the crowning feature of this work is its capacity to touch the hearts of all people. Young or old, in comfort or loneliness, amidst success or failure, we need literature, folktales, stories, and poems to take us away to that childlike dream of fairyland where everything is all at once peaceful but exciting, comfortable but brand-new, challenging but happy. “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” opens a glimpse of Wonderland, Xanadu, Bali-Ha’i, Toyland, Pixieland, Over the Rainbow, Neverland, Utopia, and Innisfree.

“The Pied Piper of Hamelin” shows a tiny glimpse of the romantic, delicate part of Browning’s heart (see Note 4). He wrote this poem to cheer a nine-year-old boy and teach little Willie to keep promises, but also to express and bequeath to him that dream of “a joyous land … just at hand.” This dream reminds us of that faraway time when we believed that people speak truth, that when you bump your knee Mom and a band-aid will fix it instantly, and that you can grow up to be anything you want to be. It’s hard to become an adult and realize that not all people are honest all the time, that some people care only about themselves and money, that the world is often too busy for relationships, that heartache is real and can bleed for a long time, and that many of your dreams still haven’t come true; but there’s a magic light that shines in your soul when you remember those simple essentials you learned so long ago and that there’s always a place to go to dream that wishes do come true.

“The Pied Piper of Hamelin” shows a tiny glimpse of the romantic, delicate part of Browning’s heart (see Note 4). He wrote this poem to cheer a nine-year-old boy and teach little Willie to keep promises, but also to express and bequeath to him that dream of “a joyous land … just at hand.” This dream reminds us of that faraway time when we believed that people speak truth, that when you bump your knee Mom and a band-aid will fix it instantly, and that you can grow up to be anything you want to be. It’s hard to become an adult and realize that not all people are honest all the time, that some people care only about themselves and money, that the world is often too busy for relationships, that heartache is real and can bleed for a long time, and that many of your dreams still haven’t come true; but there’s a magic light that shines in your soul when you remember those simple essentials you learned so long ago and that there’s always a place to go to dream that wishes do come true.I still don’t know why Browning chose to write poems about the psychologically unstable, and I’m still not sure how he and Elizabeth could have possibly been a perfect match, but as a result of my journey with “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” from Google to a child’s Paradise, I’ve found a way to connect with Robert Browning in a way that I never thought was possible. Apart from the miracle this realization has worked in my own life, the application of Browning’s “Child Story” on an adult level is valid, even imperative.

Swirling through the whirlwind of academic knowledge and world-renowned literary masterpieces, it may often seem that the piper is piping only to rats—the real world is hard, scary, ugly, and even smelly. The concepts of integrity and morality are drowned by “contemporary,” “modern,” “innovative,” and “21st century” styles of society, business, and art. It is at these times, when we are bogged down with the weight of the responsibilities, priorities, and changing ethics of the grown-up world that Robert Browning surprises us with a nursery tale for children and adults alike—a poetic masterpiece, a tender story, a fine moral, and an exquisite enchantment that flutters over time and space, majestic and maternal, enveloping in its eternal embrace those who remain children at heart.

Swirling through the whirlwind of academic knowledge and world-renowned literary masterpieces, it may often seem that the piper is piping only to rats—the real world is hard, scary, ugly, and even smelly. The concepts of integrity and morality are drowned by “contemporary,” “modern,” “innovative,” and “21st century” styles of society, business, and art. It is at these times, when we are bogged down with the weight of the responsibilities, priorities, and changing ethics of the grown-up world that Robert Browning surprises us with a nursery tale for children and adults alike—a poetic masterpiece, a tender story, a fine moral, and an exquisite enchantment that flutters over time and space, majestic and maternal, enveloping in its eternal embrace those who remain children at heart.Notes

1. The origin of the “Pied Piper” story is unknown, a detail lost during the Middle Ages, but a German manuscript from 1430-1450 records the “Exodus Hamelensis,” an occurrence in 1284 when 130 children strangely disappeared from Hameln, Hanover (Small ix). Literary and historical accounts of this folktale have been traced all the way to von Goethe. The story is included in Richard Vestegen Rowland’s Resitution of Decayed Intelligence Antiquities Concerning the English Nation, first printed in 1605. Browning’s specific source for the story was Nathaniel Wanley’s The Wonders of the Little World, or A General History of Man, printed in 1678 (Harrington).

2. The volume that Mr. Browning the elder read from was Nathaniel Wanley’s The Wonders of the Little World, or A General History of Man. When asked about retelling a story that has been around for centuries, Browning willingly attributed the original tale to other earlier accounts of it; he said, “I give mine Author’s very words: he penned, I reindite” (DeVane 535).

3. … exciting narrative, various audience, chaos of language, spirit, Hubibrastic invective, animal imagery, keen insight, clever verse, speaking voice, and exemplified narrative--I wasn’t kidding when I said everyone has something to say about Browning! These phrases of Browning’s writing in “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” are found in the following sources: Cohen 26; Erickson 82, 91, 93; Small xi; Jack 83, 84, 96.

4. Ian Jack stated in his book Browning’s Major Poetry that “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” is an ingenious work in which “the narrator appears to be indistinguishable from the poet himself,” a vast contrast from most of his other works (Jack 79).

References

Abrams, M.H. Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume 2, 7th ed. W.W. Norton: 2003.

Brooke, Stepford A. The Poetry of Robert Browning. Crowell: New York, 1902.

Cohen, J.M. Robert Browning. Longmans, Green: London, 1952.

DeVane, William Clyde. A Browning Handbook. Appleton-Century-Crafts: New York, 1935.

Erickson, Lee. Robert Browning: His Poetry and His Audiences. Cornell: Ithaca, 1984.

Harrington, Vernon C. Browning Studies. Badger: Boston, MCMXV.

Jack, Ian. Browning’s Major Poetry. Oxford: Clarendon, 1973.

Small, Terry. The Pied Piper of Hamelin. Gulliver Books: San Diego, 1988.

No comments:

Post a Comment